Thinking out loud about churn

In software as a service, churn plays a major role when analyzing cash flows and creating forecasts. The simplest way to define it, is as the percentage of number of users that have unsubscribed from the service in a given time frame. This definition works best when all users represent the same value (for instance, they all pay the same monthly subscription). When there are different tiers representing different payments for different users, churn is better defined as the proportional lost in revenues for the given timeframe.

As an example, let’s say our hypothetical saas company had 100 users at the end of the previous month and 90 at the end of this month. This means we lost 10 users out of 100, which represents a 10% decrease. If we say \(N_{0}=100\) and \(N_{1}=90\) then we generalize this as:

\[Churn_{1}=\frac{N_{1}−N_{0}}{N_{0}}\] \[Churn_{1}=\frac{N_{1}}{N_{0}}−1=\frac{90}{100}−1=−10%\]In the same way, the churn for the second month will be calculated based on the number of users at the end of month 1 and the end of month 2. So let’s imagine that by the end of month 2 we have lost 10 users again, our churn would be

\[Churn_{2}=\frac{N_{2}}{N_{1}}−1=\frac{80}{90}−1=−11.11%\]- We lost the same number of users, why is churn different?

- Well, in the second month we lost the same number of users… but from a total number that was smaller. In this case, the proportion of users lost was bigger.

- What if we assume that we lose a fixed percentage of users per month (something like 10%)?

- In that case, since the total number of users decreases the number of users we lose every month is going to decrease too.

So, let’s say we know what our churn is (based on historical data or maybe just because we want to test different assumptions). Can we find out the number of users at the end of this month if we know the number of users at the end of the previous month and our churn rate? we sure can, we just need to rearrange the previous equation.

\[N_{1}=(Churn_{1}+1) \cdot N_{0}\]Note that churn here is expressed in decimal form, so -10% is -0.01. In addition, the convention would be that churn here is a negative number. If we change this convention because we know that churn is bad so it has to be negative ;D. Then we can rearrange it again as.

\[N_{1}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn_{1})\]In our previous example we had that \(Churn_{1}=10%=0.1\) and \(N_{0}=100\) so:

\[N_{1}=100 \cdot (1−0.1)=90\]Cool, we are making progress! Can we now calculate what would be the number of users after month 12 with a constant monthly churn of 10%? Well, not yet but we are almost there… let’s try.

\[N_{1}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn)\] \[N_{2}=N_{1} \cdot (1−Churn)\] \[N_{3}=N_{2} \cdot (1−Churn)\]Yes, we would have totally made that work in excel with 12 rows where each row depends on the previous one. We could try solving it directly for just three months:

\[N_{3}=N_{2} \cdot (1−Churn)\] \[N_{3}=(N_{1} \cdot (1−Churn)) \cdot (1−Churn)\] \[N_{3}=((N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn)) \cdot (1−Churn)) \cdot (1−Churn)\]Wow, that’s feeling like a lot… let’s keep going

\[N_{3}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn) \cdot (1−Churn) \cdot (1−Churn)\]Ok, that wasn’t too bad… especially because now we can just represent it as

\[N_{3}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn)^{3}\]Which is great, because \(N_{3}\) only depends on the initial number of subscribers \(N_{0}\) and our churn rate. So now we can take a leap of faith and generalize it as:

\[N_{t}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn)^{t}\]Perfect, now we can calculate the number of subscribers at any point in time based on starting point and churn rate.

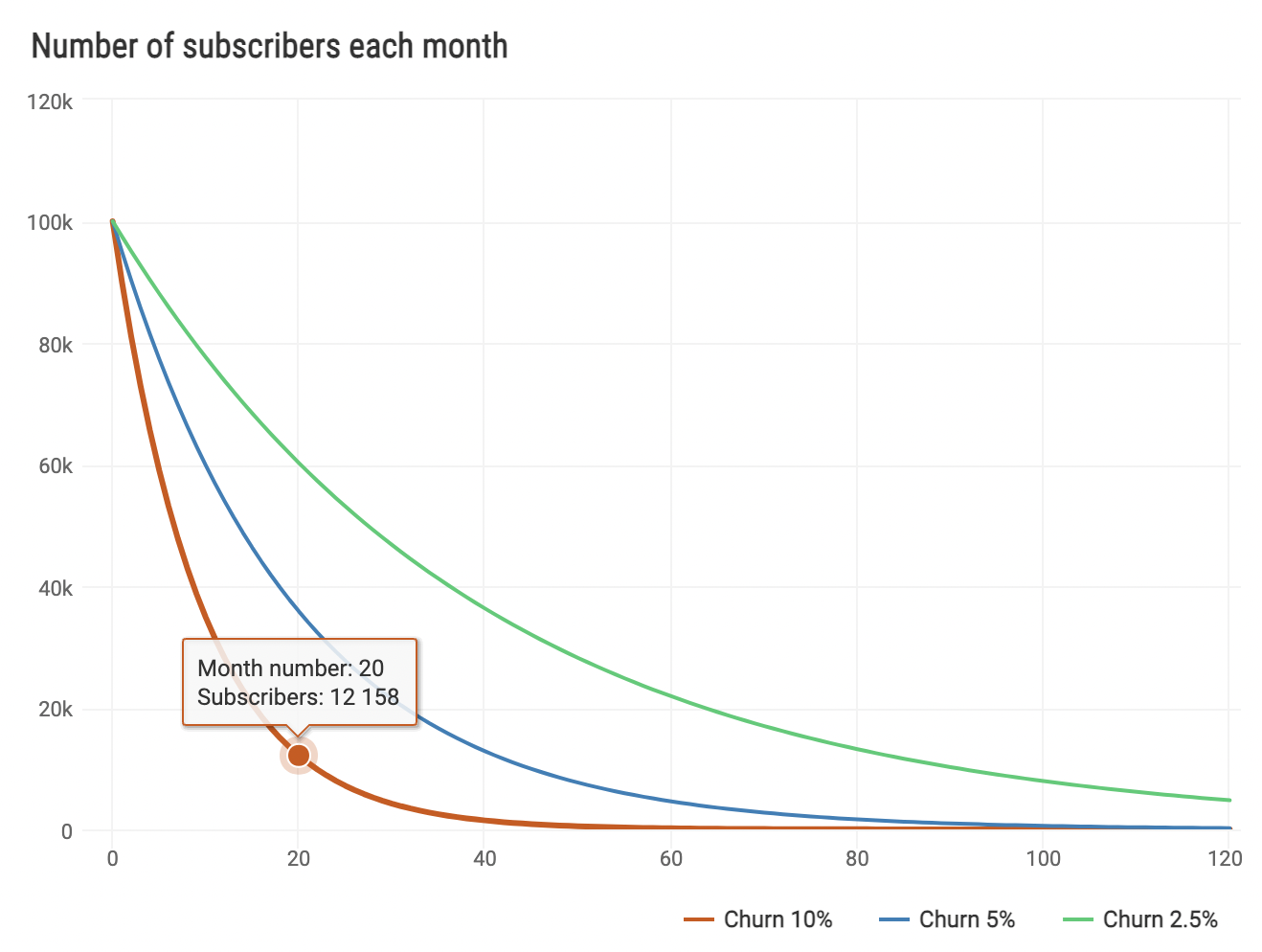

But charts are soooo much better, let’s do one and start with \(100,000\) subscribers instead of \(100\) to make rounding easier.

Once upon a time…

In what feels like a different life, I used to hang out with physicists. They have a lot of cool problems and this chart reminds me of one they called exponential decay.

The details are in the wikipedia link but the idea is that some radioactive elements decrease by an amount proportional to their current size. Sounds awfully similar, doesn’t it?

Well, they used more complex math to express and solve the formulas we saw before and this is what they obtained:

\[N_{t}=N_{0} \cdot e^{−λt}\]Now, we know that \(e−λt=(e^{−λ})^{t}\)

and we remember that the formula we found for churn was

\[N_{t}=N_{0} \cdot (1−Churn)^{t}\]We see that it’s the exact same formula… well not the exact same formula. For it to be exactly the same we should have that

\[e^{−λ}=(1−Churn)\]I am sure you are thinking “Leo, that definitely doesn’t look like the same thing” and I am right there with you, they don’t. But… maybe they could.

Here comes the number one trick for mathematicians: Taylor series.

Turns out we can rewrite \(e^{−λ}\) as an infinite sums of fractions:

\[1 − λ + \frac{λ^{2}}{2} − \frac{λ^{3}}{6} + \frac{λ^{4}}{24}\ \cdots\]If we do that and say that our λ is actually a very small number we can just ignore all terms of higher orders (this statement will put at risk any friendships you may have with particle physicists… be careful!).

Ok, if we do that we end up with:

\[e^{−λ}=1−λ\]Which means our churn formula and the fancy exponential decay are actually the same!!

I hear you, I hear you… “Leo, this sounds like the most obscure and useless piece of information I have read today… there go 5 minutes I am never getting back”.

Well, that’s not totally wrong but there is a consolation price. Since the churn formula and the exponential decay are the same (minus the funky approximation), we can stand on the shoulders of smart physicists and use some of the other formulas they derived while doing their fancy calculations.

Mean lifetime

\[τ=lifetime=\frac{1}{λ}\]Haa!! check that out, we proved \(lifetime = \frac{1}{churn}\) in the most convoluted possible way!!

Half life

\[τ_{\frac{1}{2}} = halflife = τ \cdot \ln 2 = lifetime \cdot \ln 2 = \frac{\ln 2}{churn}\]Ok, I admit I haven’t heard any mention of half-life in saas articles but maybe we can start a trend? :D

It looks like a neat formula to answer the question: with a monthly churn of 10%, in how many months do we lose half or our current subscribers?

\[τ_{\frac{1}{2}} = \frac{\ln2}{churn} = \frac{0.693}{0.1} = 6.93\]So, with a monthly churn of 10% we will lose half our customers in 7 months.

The end?

My poor brain has definitely been over extended this evening and I have reached the limits of what I remember. I will come back at some point and add a few charts.